Often cited as the most devastating epidemic in recorded world history, the 1918/1919 influenza pandemic killed more people than World War I. By many estimates, the death toll varies widely between a staggering 20 and 40 million people—and perhaps even as high as 50 million. During this pandemic, more people died of influenza in a single year than in four years of the Bubonic Plague from 1347 to 1351. Also known as the Spanish Flu, the 1918/1919 influenza pandemic was a global disaster.

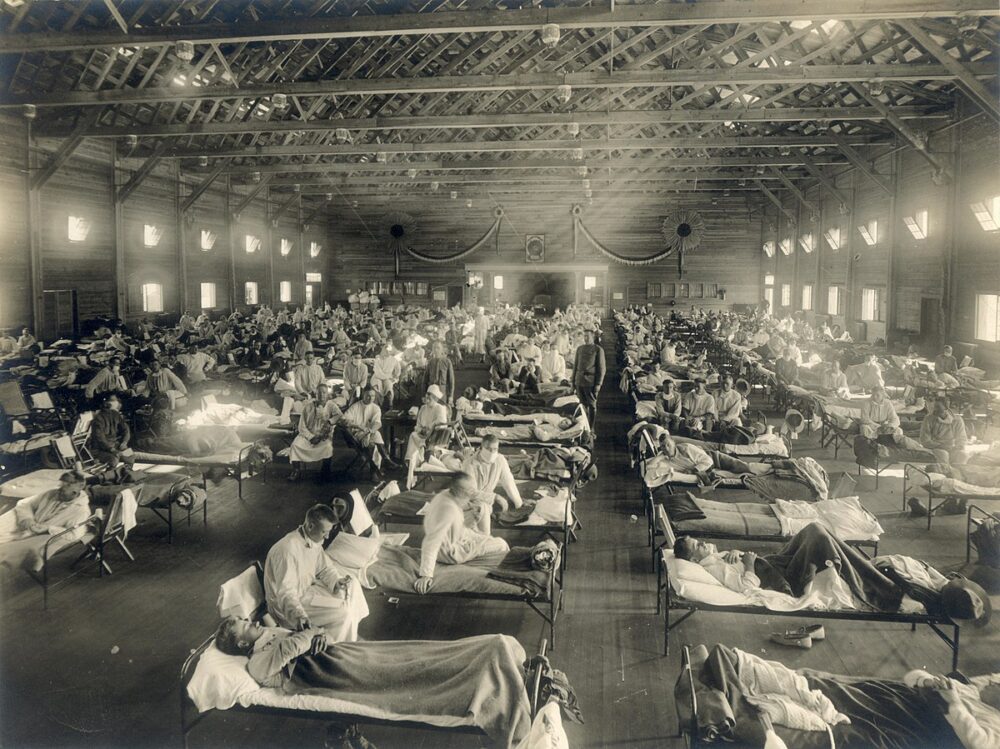

Caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin, the true source of this pandemic remains a mystery. Although we still don’t have universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, it spread around the globe in three separate waves from 1918 to 1919 as WWI was winding down. In the United States, it was first identified in military personnel at Fort Riley, Kansas, in the spring of 1918. It’s estimated that approximately 500 million people (one-third of the world’s population at that time) became infected with this virus. The actual worldwide death toll is still unknown; however, about 675,000 occurred in the United States alone—many times the number of Americans who died in WWI and more than were killed in all of the wars of the 20th century, combined.

A tale of two cities

The ways in which city officials responded to this pandemic played a major role in the death toll. The devastating second wave of the pandemic arrived on America’s shores in late summer 1918 carried by military personnel returning home from Europe, spreading first from the Atlantic coast in Boston to New York City and Philadelphia before making a westward migration to infect terrified citizens from the heartland in St. Louis, to the Pacific coast in San Francisco. There was no vaccine, and there was little to no guidance, so mayors and city health officials had to figure out what to do—from requiring citizens to wear gauze face masks, to deciding whether to close schools and ban all public gatherings, to risking the shutdown of the country’s financial centers during the final days of the war.

Many U.S. cities fared far worse than others, and looking at the evidence through the clear eyes of history shows that the earliest and most well-organized responses played a crucial role in slowing the disease spread—at least temporarily—while cities that were slow to act paid a heavier price. Nowhere is this disparity clearer than in the stories of two cities: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and St. Louis, Missouri.

Philadelphia’s Liberty Loan Parade

By mid-September 1918, the pandemic was spreading like wildfire through army and naval installations in Philadelphia; however, the city’s public health director, Wilmer Krusen, assured the public that the soldiers were only suffering from a bout of the seasonal flu that would be contained before infecting the civilian population.

Despite dire warnings from local physicians and infectious disease experts, when the first few civilian cases were reported on September 21, Krusen and his medical board responded that Philadelphians could lower their risk of infection simply by staying warm and keeping their feet dry. Civilian infection rates continued to climb exponentially daily, but Krusen refused to cancel the Liberty Loan parade that was scheduled for September 28. He downplayed the danger of spreading the disease, insisting that the parade must go on because it would raise millions of dollars in war bonds.

On September 28, a patriotic procession of soldiers, Boy Scouts, marching bands, and local dignitaries stretched two miles through downtown Philadelphia, the sidewalks packed with spectators. Approximately 200,000 people attended the parade. Although the city’s infection rate was already climbing by late September, Krusen’s decision to not cancel or postpone the parade, was like throwing gasoline on a fire. Just 72 hours after the parade, all 31 of Philadelphia’s hospitals were full and 2,600 people had died by the end of the week.

St. Louis flattens the infection curve

In October 1918, the public health response in St. Louis was completely different—thanks to Health commissioner, Max Starkloff, M.D., whose actions are credited as being an early instance in the modern medicine of social distancing. Local physicians were already on high alert, and before the first case of flu had even been reported in the city, Dr. Starkloff wrote an editorial in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch about the importance of avoiding crowds.

Dr. Starkloff is credited for closing all public venues and prohibiting public gatherings of more than 20 people in October 1918. When a flu outbreak at a nearby military barracks first spread into the St. Louis civilian population, he immediately ordered the closing of all schools, shuttered movie theaters and pool halls, and banned all public gatherings. There was pushback from business owners; however, the mayor and Dr. Starkloff held their ground. When the anticipated increase in infections occurred, thousands of sick residents were treated at home by a network of volunteer nurses. Because of these precautions, St. Louis public health officials were able to flatten the curve and keep the flu epidemic from exploding overnight as it did in Philadelphia and completely overwhelming the city’s capacity to treat patients.

In a 2007 analysis of 1918/1919 influenza pandemic death records, the peak death rate resulting from the flu in St. Louis was just one-eighth of Philadelphia’s. Still, St. Louis didn’t survive the epidemic unscathed, and this city that bills itself as the Gateway to the Midwest was hit hard in the late winter and spring of 1919 when this deadly flu returned for its third and final wave. Even so, without the precautions recommended by Dr. Starkloff, the death toll would have been so much higher.

What future generations can learn from the past about social distancing

The 1918/1919 influenza pandemic affected people around the globe. With one-quarter of the US and one-fifth of the world infected, it was impossible to escape the illness. Those lucky enough to avoid infection had to comply with public health ordinances intended to reduce the spread of the disease; however, the pandemic’s wartime arrival may have helped as much as it exacerbated the virus’ spread.

Nations were already attempting to deal with the effects and costs of WWI, and the public was more accepting of government authority, which enabled public health departments to step in and implement restrictive measures. People had been putting the needs of the nation ahead of their personal needs and were already accepting strict measures and limitations imposed by rationing and the draft. The medical and scientific communities who were already in overdrive treating the wounded were well-positioned to develop new theories and apply them to prevention, diagnostics, and the treatment of influenza patients.

A cautionary tale from a third city

San Francisco enforces the use of masks

During the 1918/1919 influenza pandemic, public health officials in San Francisco put their full faith behind gauze masks. California governor William Stephens went so far to declare that it was every American citizen’s patriotic duty to wear a mask. San Francisco leaders eventually enacted this law, and any citizen caught in public without a mask—or wearing one improperly—was arrested, charged with disturbing the peace, and fined $5, a steep sum at that time.

In reality, the gauze masks that city officials claimed were 99 percent resistant to influenza were barely effective. San Francisco’s relatively low infection rates in October were more likely due to well-organized campaigns to quarantine all naval installations before the flu arrived, as well as their efforts early in the pandemic to close schools, ban social gatherings, and temporarily shut down all places of public amusement. Pretty much, government-mandated social distancing.

On November 21, 1918, a whistle blast signaled that San Franciscans could finally take off their masks, and the residents did so willingly. However, the city’s luck ran out when the third wave of the flu struck in January 1919. Believing masks had saved them in 1918, businesses and theater owners fought back against public gathering orders, and San Francisco ended up suffering some of the highest death rates in the nation.

A 2007 study found that if San Francisco officials had retained all of its anti-flu protections through the spring of 1919, they could have reduced deaths by 90 percent.